How to select the right experiment for your project

There is so much waste in enterprise software. Teams build and build. And build. And build. But when they finally release, the product often falls flat. No one should be surprised by the fact that the vast majority of custom software development projects ($440 billion in 2019 alone!) fail

Agile — and now SAFe promised a better approach to building software — but unfortunately these processes, which have helped deliver a lot of features didn’t result in better products. What if instead of measuring how many features you are able to crank out, you looked at what would have the most impact on your business? How different would your life be if you had confidence that what you were building would actually lead to those business results before you invested?

What if we told you that you CAN have confidence and that getting more clarity on what features to prioritize is something any team can do, simply and effectively? One of the primary goals of our Experiment Driven Design process is to produce digital products that maximize business outcomes while minimizing the cost to get those results.

You may think that you need a full financial analysis to get clarity, but we love this 5×5 matrix by Hias Wrba, @ScreamingHias exercise to help guide our experiment selection.

On the Y-axis you have what amounts to your money. And on the X-axis you have your company’s money. It poses the question: “how much would you bet on this feature or epic or idea? Would you bet a round of drinks? How about a vacation?” On the other hand, “how much of the company’s money will it cost to build that? Will it cost a month of your salary or a house down payment?”

If you aren’t confident in the potential value of a feature and it is going to cost a lot to build, then you should start by understanding the opportunity more with your customers. In another scenario, you might be reasonably confident in the value, but uncertain about potential technology, schedule, or financial risk. Now that you have a better understanding of what you know and don’t know, the next question is what are you going to do to confirm that value, or to reduce risks in delivery?

One way of thinking about the best way to get more clarity is by looking at an adaptation of Giff Constable’s Truth Curve. On Giff’s truth curve, we see the believability of the outcome increase with the effort of the activity. We’ve adapted the chart below to replace believability with your level of confidence. As your confidence grows, so should the fidelity of the experiment you are running. The goal is to increase your confidence to the next step with as little effort (cost) as possible.

Now that you know it’s not only possible, but relatively straightforward, let’s dive into some actual experiments:

Paper Prototype

Paper prototyping is a great way to learn more about your idea but in a very rough format. In paper prototyping, you use literal sketches on paper and interview users 1-1 to gather feedback. Based on where they pretend to tap you can replace the screen. Alternatively, you can use a tool like POP prototyping or Invision to wire them up digitally. With paper prototyping, you’ll be gathering primarily qualitative information so roughly 5 interviews are what you should aim for.

The beauty of paper prototyping is that anyone can test an idea this way with no technical background. Trust us, you will be amazed at what you learn by simply committing the idea to paper and asking for feedback from outside your own bubble.

Example of Paper Prototyping for a project in Field Service Operations

Online Ad

A very simple way to test your value proposition and the messaging around it is to create a basic ad campaign using Facebook or Google, where you can easily target specific customer segments. Like paper prototyping, this can be done with relatively little effort and just one person. Online ads are frequently paired with a landing page if you are starting a product from scratch. Unlike interviews where you collect qualitative feedback on the why, online ads allow you to quickly gather quantitative data. You will look primarily at click-through-rate (CTR), but can also look at other metrics like conversion rate and cost-per-click (CPC).

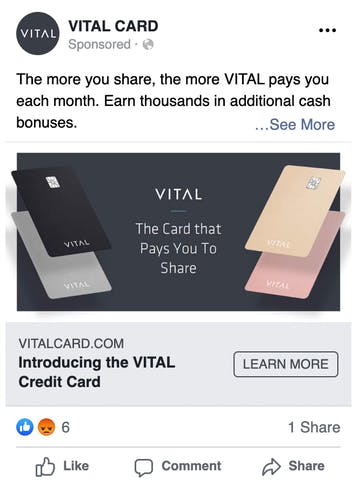

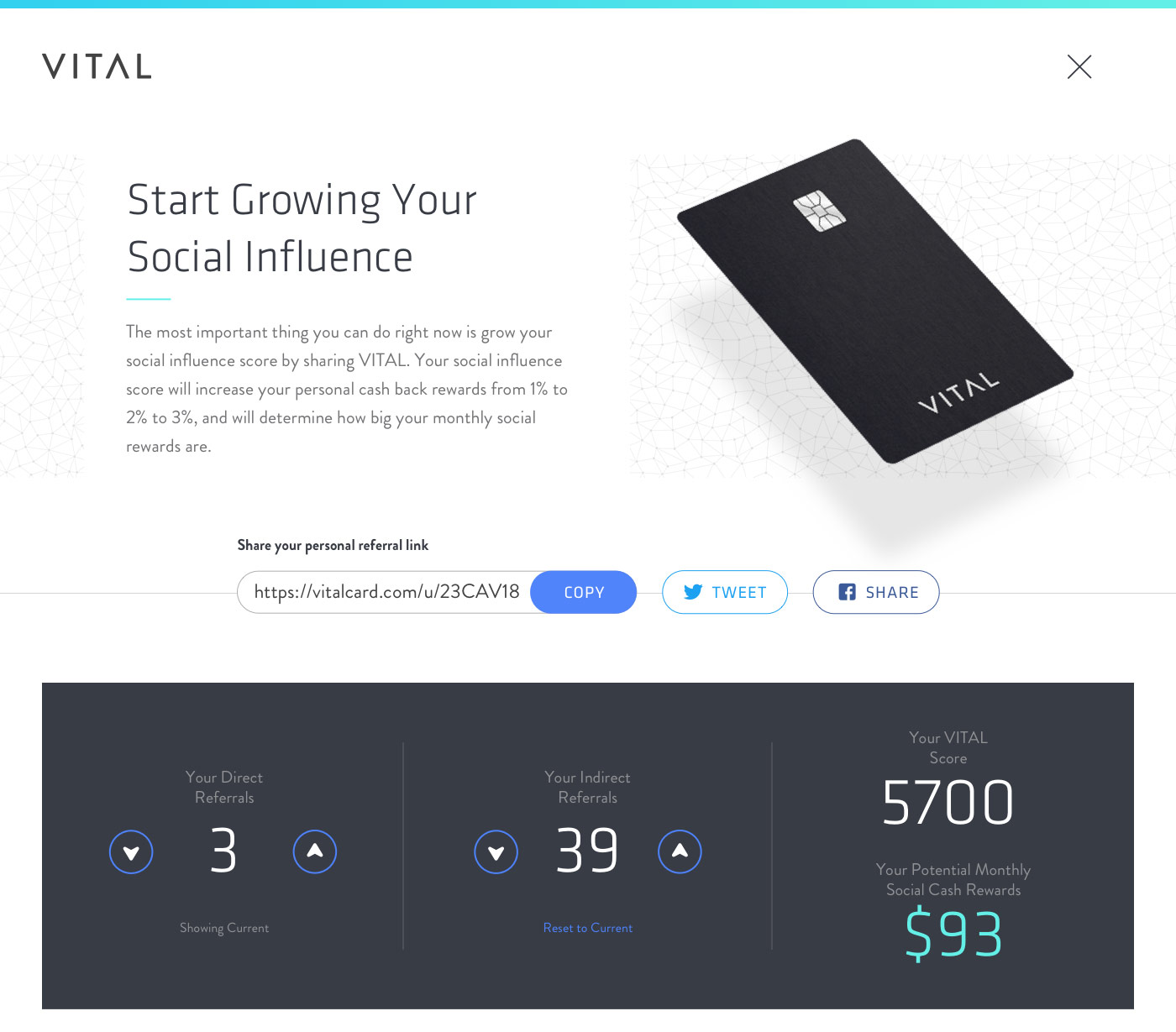

When we were helping VITAL Card with one of the most successful pre-launch campaigns ever, we did lots of experimenting with online ads. Below you’ll see one of the early examples. Not only did we use online ads to test the overall value prop, but we also used it to test demographics and early feature concepts. For example, we had a hypothesis that socially conscious people would want to give a portion of their cashback to charities. The data showed that this feature didn’t attract the same interest as some of our other ideas. For example, targeting sharing economy participants like Uber and Lyft drivers were lucrative and ended up being one of the keys to our success.

Early online ad experiment that we ran for Vital Card

Button to Nowhere

If you’ve already got an offering online, the Button to Nowhere experiment —also known as the 404 test, fake door MVP or smoke test — is a great way to gather quantitative metrics on the desirability of a potential new feature. In a button to nowhere test, you put a link or button on your site, which leads to… nowhere. To be gracious to your user, you’ll likely show an error or coming soon message. It is most frequently used on more established sites, but can also be paired with a landing page. Like online ads, you’ll track the metrics of people clicking on it so this will get you a baseline of quantitative data.

The button to nowhere is definitely not for every company and we certainly think companies should be thinking about playing with customer expectations. That being said, it is an easy way to get quantitative data on a feature’s interest with very limited work. And as you can see in the example below, it’s even used by the tech giants like Facebook and Google!

Landing Page

The next level of fidelity is the landing page. This is where you create a landing page that tells the story of your product or service and tries to get interested people to sign up. At the very least, you can just have them enter their email. Landing pages allow you to collect quantitative and qualitative data. You can send traffic to the landing page from online ads and measure the conversion rates and other analytics. Using a service like Hotjar you can look at screen recordings. And you can run 1-1 user interviews with potential users to gather qualitative feedback.

There are a number of tools that exist that let you quickly build good looking landing pages without needing a designer or engineer. They also let you run A/B tests. My personal favorite is Unbounce.

Like all of the experiments we’ve discussed so far, you can use a fake brand to remove the brand risk by learning about a product that doesn’t exist. This is especially important if you are working in a regulated industry and is one of our favorite techniques to rapidly experiment in industries like financial services and healthcare.

Early Landing page for Vital Card

Guerilla Usability

Usability tests can be run at any point in the cycle and will be something you will continue to do through launch. But you can do your initial tests with very rough shell products. In a usability test you are collecting qualitative information about your product by conducting a 1-1 interview with a potential user where you have them try to complete tasks on your prototype. Research shows that testing with just 5 people captures the vast majority of the issues. For much more detail on usability and usability testing check out Steve Krug’s seminal book on the topic Don’t Make Me Think.

Prototype

If you are reading this post you have undoubtedly heard of prototyping before. A prototype can range in fidelity from design only to be coded. With tools like Figma and Invision, you can wire design prototypes together to be interactive. Coded prototypes greatly increase the realism – after all a digital product can be experienced in code and let you do more sophisticated things like work with real data. With a prototype you’ll typically collect qualitative data, again through 1-1 interviews where you have potential users interact and complete certain tasks, understanding their thoughts and needs as they use it. Because prototypes cover such a wide range of concepts, technology, and fidelity, we’ve covered how to choose the right type of prototype to match the circumstances elsewhere.

Part of one of the prototypes we used on Vital Card that ended up being built after validation

Pre-Selling

If there is one rule of customer research, it’s “talk is cheap.” We’ve seen countless examples of clients running testing where the customer ends the test by proclaiming how awesome the product is, but then no sales materialize at launch! Pre-selling is when you sell your product before you have made it yet — after all, if your idea is really so great, why wouldn’t a potential customer commit to buying it?. This is a great way to do price discovery and also validate that people actually want what you are going to make. It might sound weird, but the advent of Kickstarter and Indiegogo, demonstrates that people will do it if the value proposition is strong enough. You don’t need to use these tools though. You can create a letter of intent contract that you try to get signed that says if I make this product, you agree to purchase it for a said fee. You pair this with a pitch deck or a prototype. You could even have a landing page that collects upfront money for pre-orders.

Proof of Concept

When you have a larger or complex product, sometimes you need to bring it to life more than a prototype, but you don’t want to invest in building the full experience. This technique is commonly used by early-stage startups looking to raise a round and enterprises using proof of concepts to generate sales. It can be tied to pre-selling as well. A proof of concept is generally more robustly built than a prototype and can look like it is fully functioning. In reality, it is mostly smoke and mirrors with elements not fully built out. It typically needs to be used following a script or a set of happy path flows. Proof of concepts also are a good way to test the technical feasibility of an idea.

Concierge MVP and Wizard of Oz MVP

Concierge and Wizard of Oz MVPs let you launch a real product, but the secret sauce is handled manually. Philosophie’s former Director of AI, Chris Butler, wrote a great post on these experiments. There are many famous examples of this such as Zappos where the founder took photos of shoes and put them on an eCommerce store. He didn’t actually own any of the inventory or have wholesale deals. When someone bought a pair of shoes on Zappos, he went to the shoe store, bought it at retail, and mailed it to his customer. The Wizard of Oz MVP is a great tool to test chatbots. Instead of spending an inordinate amount of time building out a robust conversational AI product, you can have humans on the other end. This lets you learn about the type of questions and responses customers ask. You can continue to use scripts to mirror a bot when you are learning but adjust the content more rapidly.

Pilot

A pilot is when you have a fully functioning product (or portion of a product) and release it to a small subset of users. It obviously still takes a fair amount of work to get a pilot ready, but this will let you understand more about your product before you fully launch. This helps you limit the added challenges of enterprise-scale, edge cases and robust functionality. We try to work with our clients to hone in on the smallest possible feature set to launch a pilot with, knowing that we’ll be learning and iterating from there With a pilot you collect both quantitative data in the form of analytics as well as qualitative data by constantly speaking to your pilot users.

Based on user feedback you can continue to build features and roll out to more users.

Full Product Launch

This is what most companies start with. They build the whole damn thing and let the market validate it. As one of our client stakeholder’s recently said:

“I just can’t spend 12-16 months building a solution nobody uses…AGAIN.”

We hope we’ve convinced you that it doesn’t have to be this way. You can learn what you don’t know, so you don’t build products and features that nobody wants.

Each of the steps to this point have been to increase your confidence so that when you do finally launch you will have the highest chance of success. During each of the other experiments, you likely will have identified changes to your product to make it better. Some of your early assumptions will be correct and others will have been invalidated. By iterating as opposed to just going straight to launch you will have a more refined feature set. Just like you will want to do the least amount possible to increase your confidence and learn, likewise when you launch a new product you should try to do as little as possible and focus on delivering a great result.

For each of these experiments, you need to track them against a plan to be able to invalidate or validate them. You can use our Experiment Dashboard to track progress. Your level to validate or invalidate an idea will depend on the precise concept. You aren’t going to get 100% adoption so you need to set your thresholds based on the type of experiment you are running and the expected size of the opportunity. This is why getting qualitative feedback from interviews is so important.